Oxazolidinone Antibiotics: What They Are and How They Work

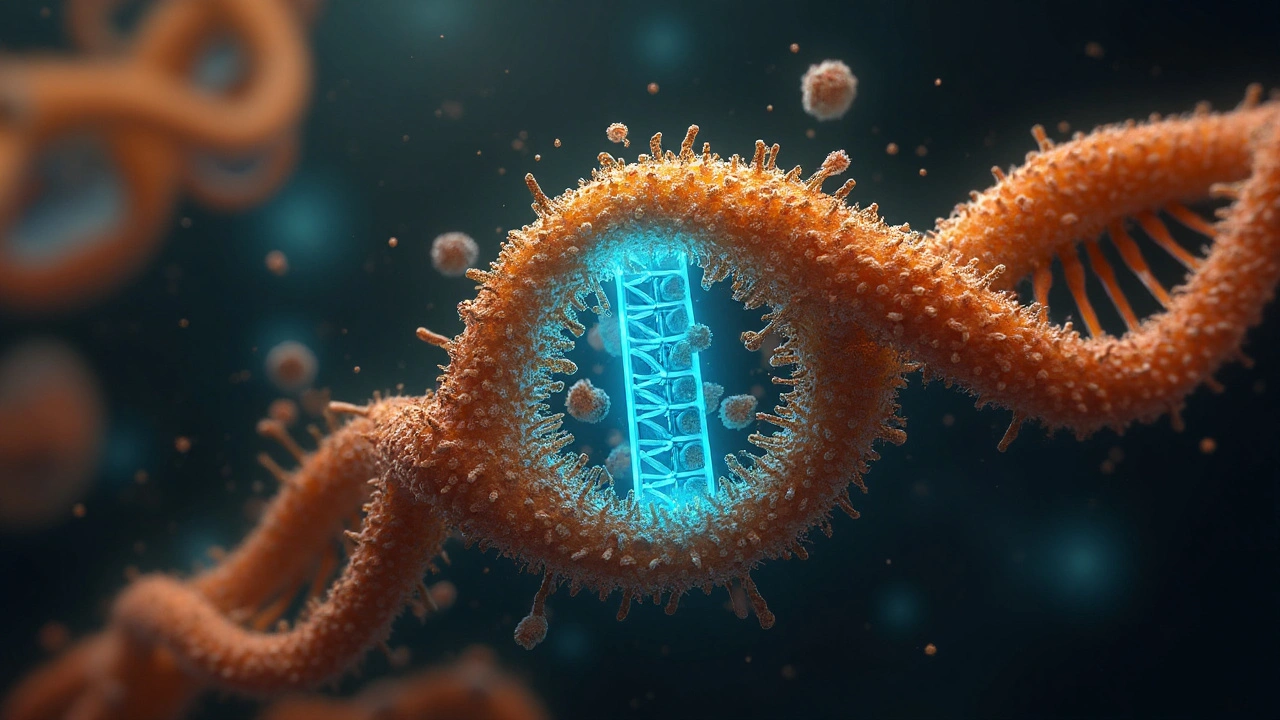

If you’ve ever been prescribed a pill called linezolid or heard a pharmacist mention “oxazolidinone,” you’re looking at a small but powerful class of antibiotics. Unlike penicillins or cephalosporins, oxazolidinones target the ribosome – the protein‑making machine inside bacteria – and stop it from building essential proteins. That simple block kills the bug or stops it from multiplying, which is why these drugs are a go‑to for tough, resistant infections.

What makes oxazolidinones stand out is their ability to get into places many other antibiotics can’t, such as the lungs, skin, and even bone. Because they’re synthetic (made in a lab) rather than derived from natural sources, scientists could tweak the molecule to hit specific bacteria while sparing the body’s own cells. The result is a class that’s especially useful against Gram‑positive bugs like Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA) and Enterococcus species.

Common Oxazolidinone Drugs

The two oxazolidinones you’ll see most often are linezolid (Zyvox) and tedizolid (Sivextro). Linezolid has been around since the early 2000s and is taken twice a day for 10‑14 days, usually as a pill or an IV drip. It’s approved for skin infections, pneumonia, and infections that spread through the bloodstream.

Tedizolid is the newer kid on the block. It’s taken once a day for a shorter course – typically six days – and tends to cause fewer blood‑related side effects. Doctors often reach for tedizolid when a patient can’t tolerate linezolid’s longer schedule or when they’re worried about rare but serious issues like low platelet counts.

Both drugs share the same basic action, but the dosing differences matter. If you miss a dose of linezolid, you usually just resume the normal schedule. Missing a dose of tedizolid, however, can drop the drug levels below what’s needed to keep the infection at bay, so it’s best to stay consistent.

Safety Tips and What to Watch For

Oxazolidinones are generally safe, but they do come with a handful of warnings you should know. The biggest red flag is the potential for blood‑cell problems – linezolid can lower red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets, especially after two weeks of use. That’s why doctors often run a quick blood test before you start and again if you’re on the drug for more than a week.

Another quirk is that linezolid can interact with foods high in tyramine (like aged cheese, cured meats, and some wines). Because linezolid blocks an enzyme that breaks down tyramine, you might get a sudden headache, high blood pressure, or a pounding heart if you eat those foods while on the drug. Tedizolid doesn’t have this restriction, which is a nice bonus.

If you notice any of the following, call your doctor right away: persistent nausea, diarrhea that won’t stop, unusual bruising or bleeding, or any signs of a rash that spreads quickly. Most side effects are mild and go away after you finish the medication, but catching problems early helps keep you safe.

Finally, remember that antibiotics, including oxazolidinones, only work against bacteria. They won’t help with viral infections like the common cold or flu, and taking them when you don’t need them can drive resistance. Use them only when a doctor says it’s necessary, and always finish the full course.

In short, oxazolidinone antibiotics are a modern, effective tool for hard‑to‑treat bacterial infections. Knowing the names, how they’re taken, and what side effects to watch for puts you in control of your treatment and helps you get back to feeling normal faster.

Linezolid Mechanism of Action: In‑Depth Review of How This Oxazolidinone Stops Bacteria

A detailed look at linezolid’s mechanism, its interaction with bacterial ribosomes, clinical implications, resistance patterns, and how it stacks up against similar drugs.