Introduction to Dopamine and Parkinson's Disease

As someone who has been fascinated by neuroscience, it's always been a point of interest for me to learn about the intricacies of our brain and how its chemicals play a pivotal role in our well-being. One of these chemicals, or neurotransmitters, is dopamine. In this article, I will be discussing the role of dopamine in Parkinson's disease, a neurological disorder that affects millions of people worldwide.

The Function of Dopamine in the Brain

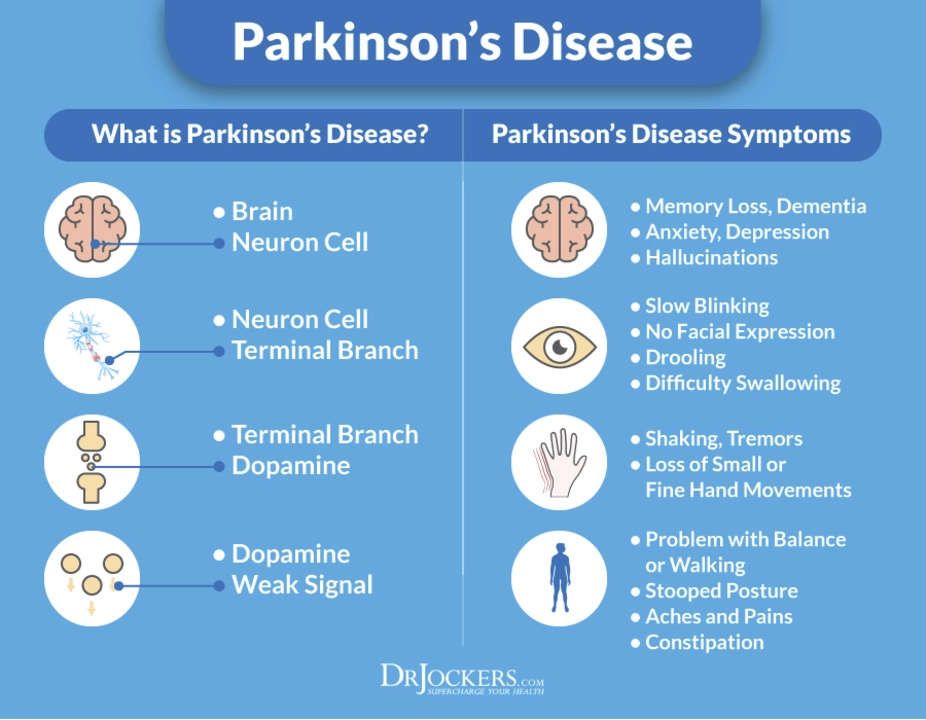

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a vital role in many of our brain functions, including movement, motivation, and reward. It is produced in several areas of the brain, including the substantia nigra, which is responsible for controlling movement. Dopamine is responsible for transmitting signals between nerve cells, and it has a direct impact on our ability to move fluidly and smoothly.

When it comes to Parkinson's disease, the primary issue lies in the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra. This degeneration leads to a decrease in dopamine levels, which in turn results in the various motor symptoms experienced by Parkinson's patients.

How Parkinson's Disease Affects Dopamine Production

Parkinson's disease is a progressive neurological disorder that affects the nerve cells responsible for producing dopamine. The exact cause of the disease is still unknown, but it is believed that a combination of genetic and environmental factors may play a role. As dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra die or become impaired, dopamine levels in the brain decrease. This decrease in dopamine production leads to the characteristic motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease, such as tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with movement.

As the disease progresses, dopamine levels continue to decline, and these symptoms worsen. It is important to note that while low dopamine levels are directly related to the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease, other non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive issues and mood disorders, can also result from the loss of dopamine-producing cells.

Motor Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease

The motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease are directly related to the decrease in dopamine production. These symptoms are what most people associate with the disease and include:

- Tremors: Involuntary shaking or trembling, typically starting in the hands or fingers

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement and difficulty initiating movement

- Rigidity: Stiffness or inflexibility of the muscles

- Postural instability: Difficulty maintaining balance and an increased risk of falls

These motor symptoms can range from mild to severe, and they tend to worsen as the disease progresses. As dopamine levels continue to decline, the severity of these symptoms increases, making daily tasks increasingly difficult for those with Parkinson's disease.

Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease

In addition to the motor symptoms, Parkinson's disease can also cause a range of non-motor symptoms. Some of these non-motor symptoms may be related to the decrease in dopamine production, while others may be the result of the overall degeneration of brain cells. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease include:

- Cognitive difficulties: Problems with memory, concentration, and decision-making

- Mood disorders: Depression, anxiety, and apathy

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia, sleep apnea, and restless leg syndrome

- Autonomic dysfunction: Issues with blood pressure, digestion, and bladder control

While these non-motor symptoms may not be directly related to dopamine production, they can significantly impact the quality of life for those with Parkinson's disease. Addressing both motor and non-motor symptoms is crucial in the overall management of the disease.

Treatment Options for Parkinson's Disease

While there is currently no cure for Parkinson's disease, there are several treatment options available to help manage the symptoms and improve the quality of life for those affected. One of the primary goals of treatment is to increase dopamine levels in the brain, which can help reduce the severity of motor symptoms. Some common treatment options include:

- Medications: Levodopa is the most commonly used medication for Parkinson's disease, as it is converted into dopamine in the brain. Other medications, such as dopamine agonists, can also help to increase dopamine levels or mimic its effects.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): This surgical procedure involves implanting electrodes into specific areas of the brain that control movement. The electrodes are connected to a device that sends electrical impulses to the brain, which can help to regulate dopamine production and alleviate motor symptoms.

- Physical, occupational, and speech therapy: These therapies can help individuals with Parkinson's disease maintain mobility, independence, and communication skills.

- Alternative therapies: Some individuals may find relief from symptoms through alternative therapies, such as acupuncture, massage, or tai chi.

It's important for those with Parkinson's disease to work closely with their healthcare team to develop a personalized treatment plan that addresses both motor and non-motor symptoms. By understanding the role of dopamine in Parkinson's disease, we can better comprehend the complexities of this neurological disorder and work towards more effective treatments and, ultimately, a cure.

Pamela may

May 4, 2023 AT 19:54First off, let me say that this post does a solid job of breaking down the dopamine story, but there are some points that need a bit more punch. Dopamine isn’t just a "feel‑good" chemical – it’s the engine behind our basal ganglia circuitry, and when that engine sputters, every motor command gets shaky.

The article mentions the substantia nigra, which is great, but it should stress that the loss of those neurons is progressive and can start years before symptoms appear.

Also, the link between dopamine and non‑motor symptoms like depression is more than a side note; it’s a direct pathway involving the mesolimbic system.

Patients often report that medication can smooth out tremors but sometimes makes them feel jittery, which is a sign of dopamine overload in other brain regions.

It’s worth highlighting that levodopa isn’t a cure; it’s a temporary boost, and long‑term use can lead to dyskinesias – involuntary movements that are as troublesome as the original disease.

Deep Brain Stimulation, while promising, isn’t a magic wand either; the placement of electrodes must be precise, otherwise you might worsen gait issues.

The article could also include recent research on neuroprotective strategies, like exercise and certain diets that seem to preserve dopaminergic neurons.

On the genetics side, variants in the LRRK2 and GBA genes have been shown to accelerate neuron loss, which adds another layer to personalized treatment plans.

I’d also love to see a mention of how gut microbiota might influence dopamine pathways – it’s a hot topic that’s reshaping our understanding of Parkinson’s.

Lastly, the link to the JNNP paper is useful, but a brief summary of its findings would help readers grasp the clinical impact without hunting down the source.

Overall, solid foundation, but let’s not settle for a surface‑level tour – dig deeper, add more nuance, and keep the conversation moving forward.

tierra hopkins

May 12, 2023 AT 22:21I really appreciate how this post walks through both motor and non‑motor symptoms – it’s easy to forget the mood and sleep issues when we focus on tremors. The breakdown of treatment options is clear and helpful for anyone just starting to learn about Parkinson’s. Keep the optimism flowing, because every bit of knowledge empowers patients and families alike.

Ryan Walsh

May 21, 2023 AT 00:48This is a great intro for folks who aren’t into neuro‑science. Dopamine helps you move, feel motivated, and even enjoy life. When it drops, you get the classic shakes and stiffness. Good read.

Kiersten Denton

May 29, 2023 AT 03:14Interesting overview, thanks for sharing.

Karl Norton

June 6, 2023 AT 05:41Honestly, this piece feels a bit half‑hearted. It glosses over the fact that many patients experience medication‑induced dyskinesia, which can be just as debilitating as the disease itself. Also, the deep brain stimulation section is overly optimistic – the procedure carries real risks and isn’t suitable for everyone. A more critical perspective would do justice to the complexities here.

Ashley Leonard

June 14, 2023 AT 08:08I love the thoroughness, but I’m curious about emerging therapies beyond meds and DBS. For instance, there’s growing evidence that high‑intensity interval training can boost dopamine production naturally. Also, some researchers are looking at gene‑editing approaches targeting the LRRK2 gene. Including a nod to these future directions would make the article even richer.

Ramanathan Valliyappa

June 22, 2023 AT 10:34Minor note: "substantia nigra" should be capitalized only when starting a sentence. Also, "non‑motor" needs a hyphen. Otherwise, the info is accurate.

lucy kindseth

June 30, 2023 AT 13:01Great summary! To add, clinicians often use the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) to track progression and treatment response. It’s a standardized tool that helps differentiate motor fluctuations from medication side effects. Also, for patients struggling with dyskinesia, adding a COMT inhibitor can smooth out levodopa peaks. Finally, multidisciplinary care – involving physio, speech therapy, and mental health support – really improves quality of life.

Nymia Jones

July 8, 2023 AT 15:28While the article presents a seemingly neutral overview, one must remain vigilant regarding the hidden agendas of pharmaceutical conglomerates that profit from dopamine‑centric treatments. The omission of any discussion on the influence of Big Pharma in shaping research directions is a glaring oversight. Moreover, the reliance on deep brain stimulation may serve as a lucrative market for device manufacturers rather than a patient‑first solution. It is imperative that readers critically assess who benefits from such narratives.