Alcohol-Related Cancer Risk Calculator

Personal Risk Assessment

This calculator estimates how your alcohol consumption increases your risk for different carcinoma types based on current scientific evidence.

When we talk about carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts in the skin or tissues that line internal organs, often growing as a solid lump. It includes several sub‑types such as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma. Alcohol consumption is the act of drinking beverages that contain ethanol, the psychoactive ingredient in beer, wine and spirits. Regular intake of ethanol introduces a cascade of biochemical changes that can damage cells, alter hormone levels and impair the body’s DNA repair mechanisms. Connecting these two dots reveals why health authorities worldwide flag drinking as a major preventable cause of cancer.

Key Takeaways

- Alcohol is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Even moderate drinking raises the risk of several carcinoma types, especially liver, breast, head‑and‑neck and esophageal cancers.

- Risk increases with the amount of ethanol consumed; the dose‑response curve is roughly linear for most sites.

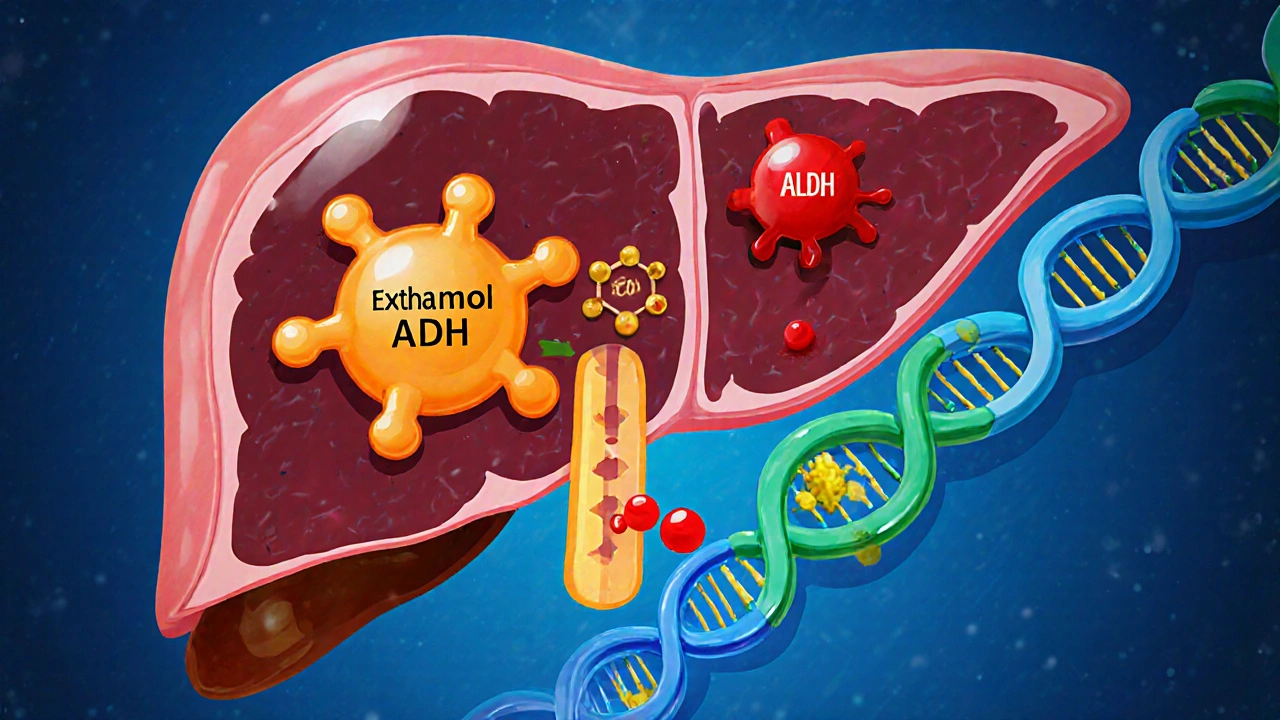

- Genetic differences in alcohol‑metabolising enzymes (ADH, ALDH) can double or halve an individual’s susceptibility.

- Cutting back to low‑risk levels (≤1 drink per day for women, ≤2 for men) or abstaining can dramatically lower carcinoma risk.

Understanding Carcinoma

Carcinomas arise when normal cells acquire mutations that let them grow unchecked, invade nearby tissue and sometimes spread to distant sites. The process usually involves three stages: initiation (DNA damage), promotion (cell proliferation) and progression (invasion). Lifestyle factors-like tobacco, diet, UV exposure and alcohol-contribute to each stage by either creating new genetic errors or weakening the body’s ability to repair them.

How Alcohol Affects the Body

When you sip a glass of wine, ethanol is absorbed into the bloodstream and sent to the liver. There, enzymes called alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) convert ethanol into acetaldehyde, a highly reactive molecule. Your body then uses aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to turn acetaldehyde into harmless acetate. If acetaldehyde builds up-because you’ve had too much to drink or your ALDH activity is low-it can bind to DNA and proteins, forming adducts that trigger mutations.

Beyond the direct DNA damage, alcohol also raises estrogen levels, increases oxidative stress, and impairs the immune system’s tumor‑surveillance role. All of these pathways are documented in peer‑reviewed studies from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Evidence Linking Alcohol to Specific Carcinomas

The scientific consensus is built on large cohort studies, meta‑analyses and mechanistic research. Below are the cancer types with the strongest evidence.

Liver Cancer (Hepatocellular Carcinoma)

Chronic heavy drinking is the leading cause of cirrhosis, and cirrhosis is a major precursor to hepatocellular carcinoma. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 45 studies found that people who consume >60g of ethanol per day (about 5 standard drinks) have a 2.5‑fold higher risk of liver carcinoma compared with non‑drinkers.

Breast Cancer

Even low‑to‑moderate drinking raises breast‑cancer risk. A pooled analysis of 53 studies reported a 7% increase in relative risk per additional 10g of ethanol (roughly one drink) per day. The mechanism involves ethanol‑induced estrogen elevation and DNA‑damage pathways.

Head‑and‑Neck Cancer (Oral Cavity, Pharynx, Larynx)

Alcohol works synergistically with tobacco. In populations that drink heavily but don’t smoke, the risk is still 1.8‑times higher than abstainers. The acetaldehyde produced locally in the mouth and throat is a key carcinogen here.

Esophageal Cancer (Squamous Cell Carcinoma)

Strong evidence links alcohol to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). In East Asian cohorts where a genetic variant of ALDH2 reduces acetaldehyde clearance, the ESCC risk can be up to 10‑fold for individuals drinking just 1-2 drinks daily.

Dose‑Response Relationship and Safe Drinking Limits

Most carcinogenic effects follow a linear dose‑response curve with no clear safe threshold. However, public‑health agencies set pragmatic limits to guide moderate drinking:

- U.S. Dietary Guidelines: ≤1 drink/day for women, ≤2 drinks/day for men.

- Australian National Health and Medical Research Council: No more than 10g of pure alcohol per day for women, 20g for men (about 1 and 2 standard drinks, respectively).

- World Cancer Research Fund: Suggests “the less you drink, the lower your cancer risk.”

For carcinoma risk, each extra standard drink adds roughly 5‑10% relative risk for breast cancer and 12‑15% for head‑and‑neck cancers.

Genetic Factors: Why Some People Are More Susceptible

Variations in the ADH1B and ALDH2 genes affect how quickly ethanol is turned into acetaldehyde and then cleared. People with the ALDH2*2 allele (common in East Asian populations) process acetaldehyde much slower, leading to higher internal exposure and dramatically higher carcinoma odds, especially for esophageal cancer.

Testing for these polymorphisms can help clinicians provide personalized advice. Even without genetic testing, being aware of family history of alcohol‑related cancers can guide more cautious drinking habits.

Reducing Your Risk: Practical Steps

- Know your limits. Stick to the recommended low‑risk guidelines or quit altogether if you have a family history of alcohol‑related carcinoma.

- Choose lower‑alcohol options. Light beers, spritzers, or diluted wine reduce ethanol intake per serving.

- Eat while you drink. Food slows alcohol absorption, lowering peak acetaldehyde levels.

- Stay hydrated. Water between drinks helps dilute acetaldehyde concentrations.

- Get screened. If you regularly consume alcohol, discuss liver function tests, mammograms and oral examinations with your doctor.

These habits don’t eliminate risk entirely, but they can cut it in half for many people.

Quick Risk‑Comparison Table

| Carcinoma Type | Risk Increase per Drink | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Liver (HCC) | 12% ↑ | Acetaldehyde‑induced DNA adducts, cirrhosis |

| Breast | 7% ↑ | Estrogen elevation, oxidative stress |

| Head‑and‑Neck | 15% ↑ | Local acetaldehyde exposure, mucosal irritation |

| Esophagus (ESCC) | 10% ↑ (general) | Acetaldehyde accumulation, genetic polymorphisms |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional binge drinking cause carcinoma?

Binge episodes spike blood acetaldehyde levels dramatically, creating acute DNA damage. While a single binge is unlikely to start cancer on its own, repeated binge patterns significantly raise the risk for liver and head‑and‑neck carcinomas.

Is red wine safer than spirits because of antioxidants?

The antioxidant benefit of resveratrol in red wine is far outweighed by the carcinogenic effect of ethanol. Studies show no net protective effect once alcohol intake exceeds low‑risk levels.

Do non‑drinkers have zero risk of alcohol‑related carcinoma?

Non‑drinkers avoid the ethanol‑derived pathways, so their risk is essentially baseline. However, they can still develop carcinoma from other factors like smoking, diet or genetics.

How does alcohol affect cancer treatment outcomes?

Alcohol can interfere with chemotherapy metabolism, reduce immune response, and increase post‑surgical complications. Patients are usually advised to stop drinking before and during treatment to improve efficacy.

Is there a safe level of alcohol for people with a family history of cancer?

When a strong family history exists, many experts recommend limiting intake to the lowest possible level, or abstaining entirely, because genetic susceptibility can amplify alcohol’s carcinogenic impact.

satish kumar

October 14, 2025 AT 15:56While the data are persuasive, it would be remiss to overlook the confounding variables inherent in epidemiological studies; many of the cited cohorts include smokers, poor dietary habits, and socioeconomic disparities that independently elevate carcinoma risk. Moreover, dose‑response curves often assume linearity, yet a threshold effect may exist for certain organ sites. The mechanistic pathways-acetaldehyde adduct formation, oxidative stress, estrogen modulation-are well‑documented, but their relative contribution varies across populations. Consequently, blanket recommendations to “cut down” without contextual nuance risk alienating moderate drinkers who already practice responsible consumption. In short, the evidence is robust, but policy must be calibrated to individual risk profiles.

Kimberly Dierkhising

October 24, 2025 AT 09:56From a biochemical standpoint, the dose‑response relationship between ethanol intake and carcinogenesis aligns with the concept of cumulative mutational burden. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies ethanol as a Group 1 carcinogen, indicating sufficient evidence in humans. Epidemiologically, each additional standard drink per day translates to approximately a 5‑10 % relative risk increment for breast carcinoma, and up to 15 % for head‑and‑neck malignancies. Pharmacokinetic parameters such as blood‑acetaldehyde peak concentrations serve as quantitative biomarkers for risk stratification. Integrating these metrics into personalized risk calculators can empower users to make data‑driven decisions.

Rich Martin

November 3, 2025 AT 02:56Consider the existential calculus of risk: every sip is a stochastic event that nudges the probability distribution of disease farther into the tail. If we accept that mortality is the ultimate boundary condition, then voluntarily accelerating that boundary by consuming ethanol becomes an ethical dilemma. The paradox lies in cultural entrenchment-social rituals valorize drinking, while the same rituals silently erode cellular integrity. Philosophically, the choice to abstain, to limit, or to indulge reflects a broader stance on self‑governance versus external influence. Hence, the discussion transcends biochemistry; it is about agency in the face of probabilistic inevitability.

Buddy Sloan

November 12, 2025 AT 20:56Stay safe, drink responsibly 😊

Deidra Moran

November 22, 2025 AT 14:56The prevailing narrative you present, dear commentator, conveniently sidesteps the systematic suppression of adverse findings by the alcohol lobby; internal memos from major beverage corporations reveal deliberate obfuscation of acetaldehyde toxicity data. Moreover, regulatory capture ensures that “moderate drinking” guidelines are calibrated to protect industry profits rather than public health. This covert agenda explains why risk communication remains vague, allowing the industry to perpetuate mythic notions of “heart‑healthy” wine despite mounting oncogenic evidence.

Zuber Zuberkhan

December 2, 2025 AT 08:56It's encouraging to see community members taking proactive steps toward risk reduction; sharing personal limits and celebrating sober milestones can create a positive feedback loop. Peer support groups have demonstrated efficacy in sustaining lower consumption patterns, especially when cultural norms shift toward moderation. By normalizing open dialogue about booze‑related health concerns, we can collectively lower the population‑wide carcinoma burden without imposing draconian bans.

Tara Newen

December 12, 2025 AT 02:56As an American, I must stress that our national health agencies have issued explicit recommendations: no more than one drink per day for women and two for men. Ignoring these guidelines not only undermines evidence‑based policy but also jeopardizes the United States' leadership in public health. The patriotic duty of every citizen is to heed these standards, ensuring the country's longevity and competitive edge on the global stage.

Amanda Devik

December 21, 2025 AT 20:56Listen the numbers don’t lie each sip adds a silent tick to your cancer risk and the cumulative effect stacks faster than most realize reducing intake even by a single drink a day can shave years off that hidden clock therefore consider your glass as a ledger of future health

Jessica Forsen

December 31, 2025 AT 14:56Oh sure, because we all gather around a Bordeaux every evening and magically become immortal-news flash, the liver doesn’t send a thank‑you note for your “moderation” when it’s busy detoxifying acetaldehyde, and your tongue isn’t a superhero shield against mutagens.

Samantha Gavrin

January 10, 2026 AT 08:56What the mainstream media won’t tell you is that the pharmaceutical giants have a vested interest in keeping the population mildly intoxicated; a slightly compromised immune system creates a larger market for immuno‑oncology drugs. By maintaining a veneer of “social drinking” they ensure a constant demand for the very treatments that will later profit them when cancers inevitably develop.

NIck Brown

January 20, 2026 AT 02:56Your philosophical musings, while intriguing, overlook the tangible policy levers that can mitigate risk-taxation, advertising restrictions, and mandatory labeling of acetaldehyde content. Abstract discourse must translate into concrete action if we are to curb the rising incidence of alcohol‑related carcinomas.

Andy McCullough

January 29, 2026 AT 20:56Ethanol metabolism proceeds primarily in hepatocytes via the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) pathway, converting ethanol to acetaldehyde, a highly reactive electrophile that readily forms DNA adducts. Subsequent oxidation by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) yields acetate, which is less toxic and enters the citric acid cycle. Genetic polymorphisms in ADH1B and ALDH2 markedly influence the velocity of these reactions; the ALDH2*2 allele, prevalent in East Asian populations, reduces enzymatic activity, leading to elevated acetaldehyde exposure after each drink. This biochemical bottleneck explains the pronounced esophageal cancer risk observed in epidemiological studies of individuals with this genotype. Furthermore, chronic alcohol consumption induces cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and amplifies oxidative DNA damage. ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation products, such as malondialdehyde, can also form DNA adducts, compounding mutagenic pressure. In breast tissue, ethanol acts as a promoter by increasing circulating estrogen levels, thereby stimulating proliferation of estrogen‑responsive cells. The interplay between hormonal modulation and direct genotoxicity creates a synergistic environment conducive to malignant transformation. It is noteworthy that acetaldehyde is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the IARC, underscoring its central role in alcohol‑related oncogenesis. In addition to DNA damage, chronic intake impairs immune surveillance by suppressing natural killer (NK) cell activity, diminishing the body’s ability to eliminate nascent tumor cells. Epidemiological meta‑analyses consistently demonstrate dose‑response curves, with each additional standard drink per day incrementally raising relative risk for liver, breast, head‑and‑neck, and esophageal cancers. Importantly, the magnitude of risk varies by organ site, reflecting tissue‑specific susceptibilities to acetaldehyde and oxidative stress. Lifestyle interventions that reduce alcohol intake consequently lower acetaldehyde burden, restore enzymatic balance, and improve immune function. For clinicians, incorporating alcohol consumption metrics into routine risk assessments enables early identification of high‑risk individuals. Preventive strategies, such as counseling on low‑alcohol or alcohol‑free alternatives, can significantly attenuate the projected cancer burden. Ultimately, understanding the mechanistic cascade from ethanol ingestion to DNA damage informs both public health policy and individualized patient counseling.

Aminat OT

February 8, 2026 AT 14:56lol i cant belive ppl still think wine is good for u its just more booze lol u know how it maked u feel after a few nights?? its not just fun its riskin u health!!

Amanda Turnbo

February 18, 2026 AT 08:56The evidence suggests a statistically significant correlation between daily ethanol consumption and increased carcinoma incidence; however, the practical implications must be contextualized within individual lifestyle factors and genetic predispositions. While some may argue that moderate drinking poses minimal risk, the aggregated data across diverse cohorts underscores the necessity for caution.

Jenn Zuccolo

February 28, 2026 AT 02:56From a moral philosophy perspective, the act of consuming a known carcinogen raises questions about one's duty to oneself and to society; the principle of non‑maleficence, traditionally applied in medical ethics, can be extended to personal health choices. If our actions increase the likelihood of future medical interventions, we implicitly burden healthcare systems and, by extension, the communal social contract.

Herman Rochelle

March 9, 2026 AT 20:56Your emphatic call to view each drink as a “ledger of future health” resonates strongly; framing consumption in concrete, quantifiable terms often spurs behavioral change more effectively than abstract warnings.