Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Medication Risk

Total grams taken (approx. 2-3 years = 400g)

Risk Assessment Results

When Your Medicine Starts Scarring Your Lungs

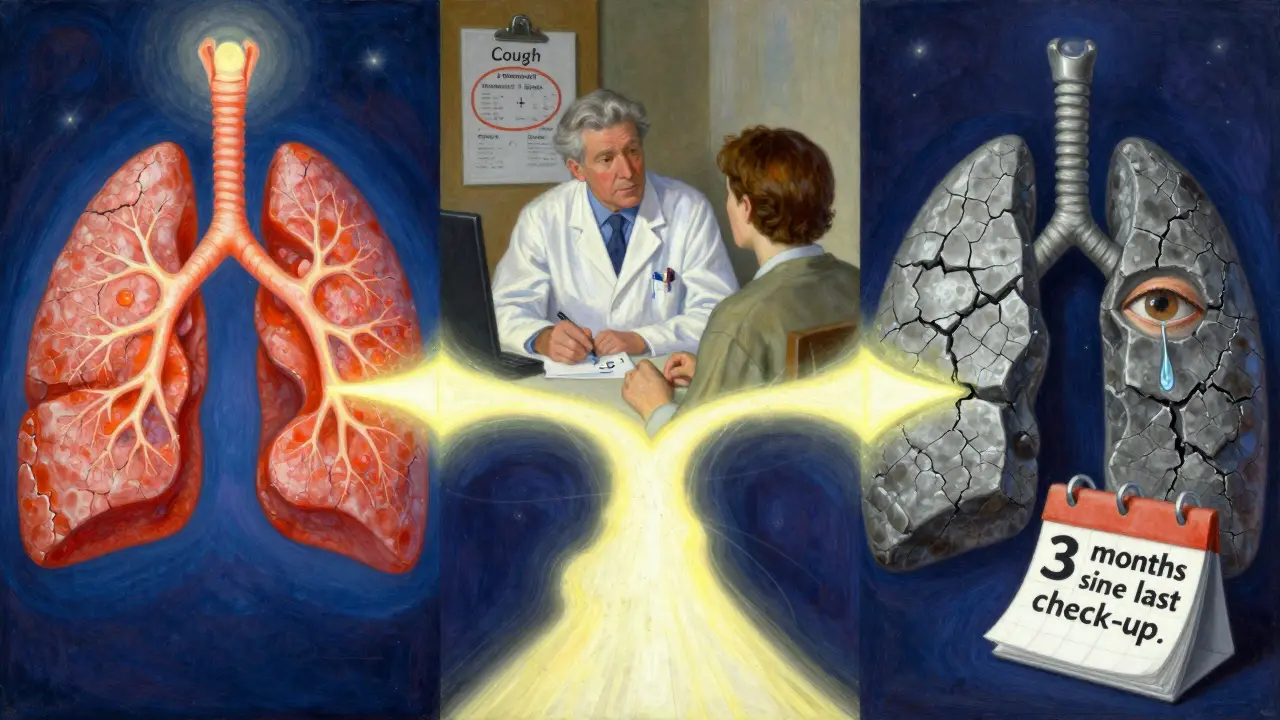

You take a pill every day to manage your arthritis, your heart rhythm, or to fight cancer. You trust it. You’ve been told it’s safe. But what if that same pill is quietly damaging your lungs-turning soft, stretchy tissue into stiff, scarred muscle? This isn’t rare. It’s called drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis, and it’s happening to people you know.

Unlike the slow, mysterious scarring of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, this version has a clear trigger: a medication. And it’s not just one or two drugs. Over 50 medications, from common antibiotics to life-saving cancer treatments, have been linked to this hidden lung injury. The scary part? Most people don’t know it’s happening until they’re gasping for air.

How a Pill Turns Your Lungs to Stone

Your lungs aren’t just sacks of air. They’re made of delicate, sponge-like tissue designed to pull oxygen into your blood. When you breathe, air flows through tiny sacs called alveoli, surrounded by thin walls that let oxygen pass into capillaries. Pulmonary fibrosis happens when those walls thicken with scar tissue-like rubber bands turning into concrete.

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis works the same way, but the cause is chemical. Certain medications trigger an abnormal immune response or directly damage lung cells. The body tries to heal, but instead of repairing, it overproduces collagen. That’s the scar. And once it’s there, it doesn’t go away.

It’s not about dosage. You can take a low dose for years and never have a problem. Then, out of nowhere, your lungs start stiffening. That’s why it’s called an idiosyncratic reaction-it’s unpredictable. One person takes amiodarone for 10 years and stays fine. Another develops scarring after six months. No one knows why.

The Top 5 Medications That Risk Your Lungs

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are rare offenders. Others are common-and dangerous. Based on data from New Zealand’s pharmacovigilance system (2014-2024), these five medications account for nearly half of all reported cases of drug-induced lung scarring:

- Nitrofurantoin (used for urinary tract infections): 47 cases reported. Often affects older adults on long-term prevention. Symptoms can appear after 6 months-or 10 years.

- Methotrexate (for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis): 45 cases. Can cause sudden, severe lung inflammation that mimics pneumonia. Up to 7% of users develop it.

- Amiodarone (for irregular heartbeats): 39 cases. Toxicity builds up over time. After 400 grams total (about 2-3 years of use), risk jumps sharply. Up to 7% of long-term users are affected.

- Bleomycin (chemotherapy): Up to 20% of patients develop lung damage. It’s one of the most dangerous cancer drugs for the lungs. Even a single dose can trigger it.

- Cyclophosphamide (another chemo drug): Affects 3-5% of users. Often hits harder in older patients or those with existing lung conditions.

And these are just the big ones. Newer cancer drugs-immune checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab and nivolumab-have been linked to lung scarring since 2011. These drugs unleash the immune system to fight tumors… but sometimes, it turns on the lungs instead.

What Symptoms Should You Watch For?

These symptoms don’t come on like a cold. They creep in. Slowly. So you blame it on getting older, being out of shape, or seasonal allergies.

- A dry, hacking cough that won’t go away-no mucus, no fever, no reason.

- Shortness of breath during simple tasks: walking to the mailbox, climbing stairs, tying your shoes.

- Feeling tired all the time, even after sleeping.

- Chest discomfort or pain that doesn’t match heart problems.

- Fever or joint aches without infection.

According to patient surveys, 78% of people with drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis report worsening breathlessness. 65% have a chronic cough. 32% get fevers and fatigue. These aren’t side effects you ignore. They’re red flags.

And here’s the worst part: diagnosis is delayed. On average, it takes 8.2 weeks from when symptoms start until a doctor realizes it’s the drug-not aging or asthma. By then, the scarring may already be advanced.

Why Doctors Miss It-And How You Can Help

A 2022 survey found only 58% of primary care doctors routinely ask patients on high-risk drugs about breathing problems. Why? Because there’s no single test for drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. No blood marker. No unique scan pattern. It’s a diagnosis of exclusion.

Doctors have to rule out everything else: infections, heart failure, autoimmune diseases, environmental exposures. That’s why your medication history matters more than you think.

Here’s what you can do:

- Know your drugs. If you’re on nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, amiodarone, or any chemo drug, ask your doctor: “Could this affect my lungs?”

- Keep a list of every medication you’ve taken in the last 12 months-including antibiotics, supplements, and over-the-counter pills.

- If you develop a new cough or shortness of breath, say: “I’m on [drug name]. Could this be related?”

- Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Early detection saves lung function.

The New Zealand Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee specifically warned doctors in September 2024: “Patients taking medicines associated with ILD should be aware of this risk and seek prompt medical attention if they develop cough, chest pain, or shortness of breath.” That’s not a suggestion. It’s a directive.

What Happens When You Stop the Drug?

The good news? If caught early, this is one of the few types of pulmonary fibrosis that can improve.

Stopping the drug is the single most important step. In 89% of cases, lung function stabilizes or improves within three months after stopping the offending medication.

But stopping isn’t always enough. If inflammation is still active, doctors often prescribe high-dose steroids like prednisone-0.5 to 1 mg per kilogram of body weight daily. That’s a heavy dose, but it’s meant to calm the immune system before it turns more lung tissue to scar.

After a few weeks, the dose is slowly lowered over 3-6 months. Too fast, and the inflammation can come back. Too slow, and you risk steroid side effects like weight gain, bone loss, or diabetes.

Some patients need oxygen therapy if their blood oxygen drops below 88%. Others need pulmonary rehab-breathing exercises, walking programs, education. It’s not a cure, but it helps you live better.

Prognosis? If caught early and the drug is stopped, 75-85% of patients make a good recovery. But 15-25% are left with permanent lung damage. That’s why timing matters.

What’s Being Done to Prevent This?

There’s growing alarm in the medical community. Reported cases of drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis have risen 23.7% over the past decade. Part of that is better reporting. But part of it is real-more drugs, more use, more risk.

Pharmaceutical companies are starting to test for lung toxicity earlier in drug development. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and Medsafe are updating warning labels. The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation launched a physician education program in 2024, and early results show a 32% drop in diagnostic delays in clinics that participated.

Researchers are hunting for genetic markers that might predict who’s at risk. If you have a certain gene variant, maybe your lungs are more likely to react badly to amiodarone or methotrexate. That could mean screening before prescribing.

But for now, the best defense is awareness. Ask questions. Speak up. Don’t assume your doctor knows.

What If It’s Already Too Late?

Some people are diagnosed after significant scarring has set in. Their lungs are stiff. Their oxygen levels are low. They’re on long-term oxygen. They can’t walk more than a few steps without stopping.

There’s no reversal. No magic pill. The damage is permanent. But that doesn’t mean hope is gone.

Pulmonary rehab can help you maximize what’s left. Oxygen therapy keeps you alive. New anti-fibrotic drugs like pirfenidone and nintedanib-approved for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-are now being studied in drug-induced cases. Early results suggest they may slow further decline.

And lung transplant? It’s an option for the youngest, healthiest patients with end-stage disease. But it’s a last resort. And it’s not easy. You’ll need to be on immunosuppressants for life.

The goal isn’t to cure. It’s to live as fully as possible-with the lungs you have.

Final Warning: This Isn’t Rare. It’s Silent.

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis doesn’t make headlines. It doesn’t have a celebrity spokesperson. But it kills. In New Zealand alone, 30 people died from it between 2014 and 2024. Many more were left with permanent damage.

If you’re on any of these drugs-nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, amiodarone, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, or newer immunotherapies-pay attention to your breathing. Don’t wait for a cough to become a crisis. Don’t assume it’s just age.

Ask your doctor. Get a baseline pulmonary function test if you’re on long-term therapy. Know your symptoms. Speak up. Your lungs can’t warn you. Someone has to speak for them.

Can you get pulmonary fibrosis from antibiotics like nitrofurantoin?

Yes. Nitrofurantoin, a common antibiotic for urinary tract infections, is one of the top drugs linked to pulmonary fibrosis. It can cause lung scarring even after years of use, especially in older adults. Symptoms may appear 6 months to 10 years after starting the drug. The risk is low overall, but when it happens, it’s serious. Stopping the drug early can prevent permanent damage.

How long does it take for amiodarone to damage the lungs?

Amiodarone-induced lung damage usually develops after 6 to 12 months of use, but it can take years. Risk increases significantly after a cumulative dose of 400 grams-roughly 2-3 years of daily use. The damage builds slowly, and symptoms like cough and shortness of breath are often mistaken for aging or heart failure. Regular lung checks are recommended for anyone on long-term amiodarone.

Is drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis reversible?

It can be-if caught early. Stopping the offending drug is the most critical step. In 89% of cases, lung function improves or stabilizes within 3 months of discontinuation. Corticosteroids may be added to reduce inflammation. But if scarring is advanced, the damage is permanent. Early detection is the only way to avoid lifelong lung impairment.

What drugs are most likely to cause lung scarring?

The top offenders are nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, amiodarone, bleomycin, and cyclophosphamide. Nitrofurantoin and methotrexate are the most commonly reported in pharmacovigilance data. Bleomycin carries the highest relative risk among chemotherapy drugs. Newer cancer immunotherapies like pembrolizumab are also now linked to lung scarring. Always ask your doctor about lung risks before starting any new medication.

Should I get a lung scan if I’m on methotrexate?

Routine lung scans aren’t standard for everyone on methotrexate-but they should be considered if you have risk factors like age over 60, smoking history, or pre-existing lung disease. More importantly, report any new cough or shortness of breath immediately. Methotrexate can cause sudden, severe lung inflammation that looks like pneumonia. Early diagnosis and stopping the drug can prevent permanent damage. Don’t wait for a scan-speak up when symptoms start.

Can I switch to a different drug if I develop lung issues?

Yes, often you can. For example, if methotrexate causes lung damage, doctors may switch you to another arthritis drug like sulfasalazine or a biologic. If amiodarone is the culprit, alternatives like dronedarone or beta-blockers may be options. But switching isn’t always simple-some conditions require specific drugs. Your doctor will weigh the benefits of the original medication against the lung risk. Never stop a drug without medical guidance.

Are there any tests to predict who’s at risk?

Not yet. There’s no blood test or genetic screen that can reliably predict who will develop drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Researchers are studying genetic markers, but nothing is ready for clinical use. That’s why awareness of symptoms and early reporting are your best tools. If you’re on a high-risk drug, know the signs-and act fast.

Jenny Salmingo

December 30, 2025 AT 16:57Paul Huppert

December 31, 2025 AT 09:59Hanna Spittel

January 1, 2026 AT 14:19John Chapman

January 3, 2026 AT 03:03Brandon Boyd

January 4, 2026 AT 18:58Marilyn Ferrera

January 5, 2026 AT 03:12Aaron Bales

January 5, 2026 AT 17:56Frank SSS

January 7, 2026 AT 10:35Branden Temew

January 9, 2026 AT 07:48Robb Rice

January 10, 2026 AT 16:43Sara Stinnett

January 11, 2026 AT 23:02Bennett Ryynanen

January 13, 2026 AT 19:36Brady K.

January 15, 2026 AT 16:40Lawver Stanton

January 17, 2026 AT 06:39Kayla Kliphardt

January 18, 2026 AT 08:09